What Happened to That Girl? A Female Manipulator Ate Her.

Thoughts | Roxana Moise

Last May, I started writing a piece about the ‘that girl’ phenomenon.

If you’ve been on Tiktok or Instagram over the past year, you’ve probably encountered it — creators, often young women with glowing skin and matching workout sets, film themselves waking up in the early hours of the morning, preparing green smoothies, journaling, and overall appearing more put-together than any of us normal people could ever hope to be. Their message: We take care of ourselves. We are productive. When the pandemic took away our externally imposed schedules, we rose to the occasion and maximized our newfound free time. The structured self-assurance of ‘that girl’ was a natural (if aspirational) response to an uncertain and previously uncharted period of time.

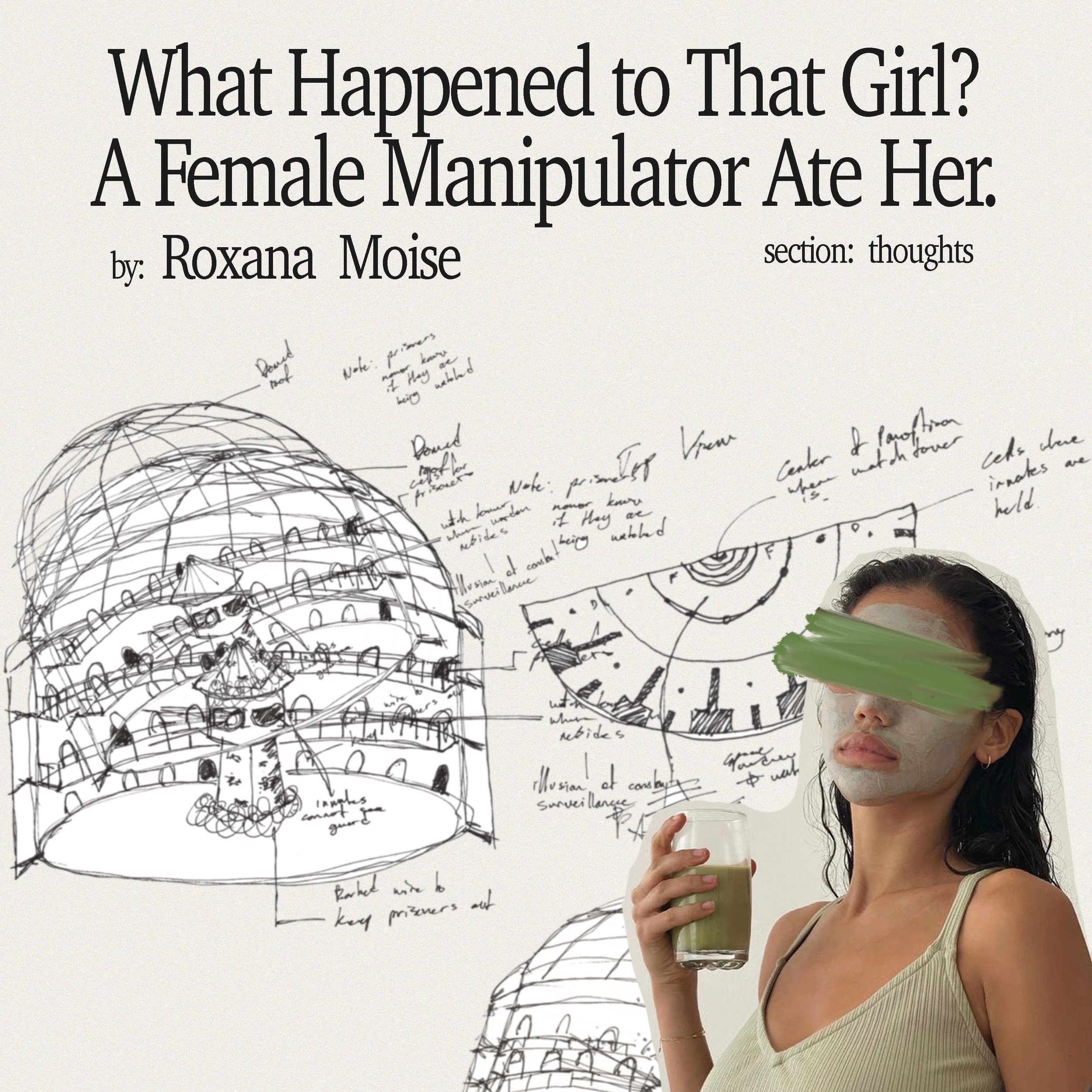

I was hoping to write about two issues I saw within the ‘that girl’ trend: firstly, the culture of aesthetics and consumerism that lurked beneath the veneer of ‘wellness’, and secondly, the way it glamourized using one’s personal time to keep grinding away. Being a young woman has always felt a bit like existing in a panopticon; you never know when there are eyes upon you, especially those of men. Do they find you pleasing? Do they find you attractive? I saw ‘that girl’ as compounding this feeling — not by itself, but as the latest trend in a movement to share more and more of yourself online.

This is not a new issue.

The advent of social media over the past decade and a half has opened the door for personal space to be commodified. Even early on, it wasn’t enough to post pretty pictures from an outing or vacation; because your smartphone came inside with you, your home was now open to the world, or at least to your followers. Your kitchen was no longer merely a space for the preparation of food, but the stage for an artfully shot cooking video; your bed, a fairy light-lit backdrop for a picture of the book you were reading. The pandemic only added fuel to the fire that had been normalized by apps like Instagram and Snapchat by transforming homes into Zoom backdrops, open to the workplace and to your colleagues. ‘That girl’ hammered the final nail into the coffin — now, in addition to the pressure to beautify your home and professional life, even your self-care needed to be beautiful. There was no more privacy to eat breakfast in your ratty old pyjamas, or become sweaty and grunt out your breaths while working out, because somewhere out there, ‘that girl’ was doing it all while looking presentable to the camera.

However, as I worked on my article about ‘that girl,’ I realized that I had missed the boat. I was too late. A counterculture that had been rising in response to ‘that girl’ was gaining more and more steam, and perhaps even eclipsing her in popularity. Instead of glamourizing productivity and improvement, this movement encouraged women to be messy, to consume sad media, and to let themselves give up on the ideal of ‘the woman who could do it all’.

The ‘toxic feminine’ had arrived.

It was a natural consequence. Any movement that put such a heavy emphasis on perfection was bound to burn people out, and in its wake, they were eager to embrace the darker side of human nature. Those who enjoyed wielding power over men claimed the title of ‘female manipulators’, and those who thought that their esoteric interests were offputting to men called themselves ‘femcels’, or ‘female incels’, regardless of how much male attention they actually received. Self-perception was, crucially, dominated by media consumption; instead of describing themselves using adjectives, people listed the artists to whom they listened and the authors whose works they read. By connecting their emotions to the idealized versions displayed in media, people’s everyday experiences were elevated. In this way, any unhappy moment or unhealthy relationship could be transformed into something hauntingly sad or beautifully toxic.

While the ‘that girl’ movement dictated that your private moments of productivity needed to be beautiful enough to present to the public, the ‘toxic female’ trend insinuated that even your private moments of anguish, of pain, or of loneliness needed to be packaged and commodified. It wasn’t enough to be sad, because you needed to be able to explain if it was in a ‘Lana del Rey’ or ‘Mitski’ or ‘Marina’ kind of way.

If someone were to peer through your window mid-breakdown, they would need to understand that you were not crying in a pathetic way, but in a ‘Sylvia Plath, female manipulator, Fiona Apple, cherry emoji, Otessa Moshfegh, cigarettes-but-the-cool-kind-not-the-kind-that-hurt-your-lungs’ kind of way.

Our identities have always revolved around the things we like. This is not inherently a bad thing, as it allows us to find community with people like us, to explore similar things, and to learn more about ourselves. It is also not a bad thing to be able to present ourselves using the platform of social media — it can make us feel cool, validate our self-identity, and again, help us find community. However, the dissemination of these things into our private lives turns much-needed moments of rest and sadness, when we might need the freedom to be messy and unpresentable, into yet another kind of performance. Our culture already pushes us to work hard, hustle, and make money instead of resting. Our contributions to the workplace are already valued more than our contributions to ourselves or to our community. In a culture like this, perhaps we can see being true to our private selves as a sort of resistance.

This isn’t to say that nobody should take videos of themselves making green smoothies, or that nobody should share that they find comfort in sad media, because expressing yourself and finding community is generally a good thing. These movements can make people feel less alone by giving them validation that yes, it is normal to struggle with the constant pressure placed on women to be caretakers, to be objects of desire, to be male fantasies. The ‘that girl’ movement rebels against this pressure by positioning the woman as the caretaker of, first and foremost, her own self. Social media posts that lean into the ‘toxic feminine’ provide the comfort of knowing that other women are struggling and breaking down too. However, it is also okay to protect your privacy, and to remember that you are not any less of an interesting and presentable person for having unwashed hair now and then, or for crying like a normal person instead of a ‘cool girl’. While you do not always have to live up to the aesthetically polished ideal of ‘that girl,’ you also do not have to fall short of it in a ‘Marlboro Reds, Norman Bates, chipped black nail polish’ kind of way.

Maybe what I’m saying is that we need to normalize being normal.

Your moments of peace and despair and determination and rest don’t have to look any certain way — the camera on your phone may be a powerful tool for connection, but you never owe it a performance. You are enough.

Author’s note: While I don’t know if she originated the term, my usage of the words ‘toxic feminine’ to describe the trend comes from Mina Le’s YouTube video on the topic, which can be found here.